As a lit major and someone who’s always loved books, I’ve long believed that stories can lead you to the most amazing places—whether for reading, writing or just exploring the spots your favourite authors once imagined. Back in college, A Passage to India by E.M. Forster was one of my go-to’s. I couldn’t get over the Marabar Caves he described—their glassy walls and strange echoes that made every sound larger than life. For years, I wondered whether these caves were real or just a clever invention of Forster’s imagination.

Fast forward to a few years later when a friend and I were visiting Bodh Gaya in Bihar. There, we heard rumours about ancient caves that seemed uncannily like the ones from the book. Curiosity got the better of us, and on a chilly winter morning, we booked a cab from Patna and set off to find out for ourselves. The road grew quieter as we left the city behind, a peaceful stretch ahead with only the occasional motorbike or tractor.

And then, after a long, winding drive, we found them—the most stunning, gorgeous, and oldest caves in India, still standing with the latest preservation technology. These weren’t just any caves; they were the Barabar Caves, the very inspiration behind the legendary Marabar Caves from Forster’s novel. It was like stepping into a world I had only read about—but this time, it was real.

Barabar caves – The oldest surviving rock-cut caves in India

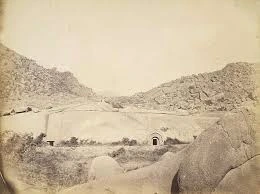

As we reached the Barabar Caves, the first thing that hit me was the silence. It was a far cry from the chaos of Patna and the hum of Bodh Gaya. The complete absence of other visitors struck me, which was quite different from the famous Bihar Buddhist circuit destinations. There was just an elderly man sitting near the gate, a red gamchha casually draped around his neck. He looked as surprised to see us as we were to find the place so empty. But with a kind smile, he offered to guide us around the ancient site.

The Barabar Caves sit atop a hill scattered with massive boulders, and one giant slab-like rock in particular houses the caves themselves. From a distance, it looked as though some giant had placed the boulder on the hill and simply walked away. The isolation was striking—just the sound of birds and the occasional breeze, as calming as the prayer chants back in Bodh Gaya. It made me wonder if this very isolation had inspired E.M. Forster when he wrote about the Marabar Caves.

Our guide then shared something that gave me goosebumps—these are the oldest surviving rock-cut caves in India, dating back to the time of Emperor Ashoka in 260 BC. As we explored further, he pointed out each of the four caves: Sudama, Lomas Rishi, Karan Chaupar, and Visvakarma. The Sudama cave, dedicated by Ashoka himself, has an incredible bow-shaped arch and a circular vaulted chamber. Meanwhile, the Lomas Rishi cave, with its intricate facade mimicking ancient timber architecture, features a row of carved elephants marching toward stupa emblems. As I stood there, surrounded by centuries of history, it felt like I had stepped back in time, to a place where legends and architecture came alive.

Constructed by Emperor Ashoka for Ajivaka ascetics

“These caves were built by none other than Emperor Ashoka (who reigned in 273 – 232 BC),” the guide began, pausing to gesture toward the cave’s entrance. “Not for Buddhists, as many assume, but for the Ajivaka ascetics, a forgotten sect that once rivalled Buddhism and Jainism.”

King Ashoka and his son Dasaratha were Buddhists but their state had religious freedom. Several Jain sects and branches flourished in this time among other religious and philosophical trends. One such trends was Ajivika (Ājīvika) – considered by many to be a separate belief – in some respects rather an atheistic movement in philosophy.

He explained that Barabar is considered the birthplace of the Ajivika sect, and Ashoka himself dedicated the Sudama Cave to the Ajivika monks in 261 BC. “You can still see Ashoka’s inscription in the Sudama Cave,” the guide pointed out.

This deeply ascetic movement originated a few centuries earlier together with Buddhism and was characterized by a belief in determinism. In Hinduist and Buddhist sources, practitioners of Ajivika were presented as strict fatalists. Father of Ashoka was a believer of this philosophy and during Ashoka’s time, it reached its peak of popularity. This belief has not survived up to this day and in fact, there is little known about it. Unfortunately, no original scriptures of this ancient philosophy have survived. “They were once powerful,” he added, “but like many ancient philosophies, they faded into history.”

The Buddhist connection in the Lomas Rishi Cave

Moving to the Lomas Rishi Cave, the guide pointed to its entrance. “This one is different,” he said with a smile. “Lomas Rishi is connected with Buddhism. Look at that arch—it’s called a chaitya arch, and it’s the oldest one of its kind. The Buddhists used these in their architecture, even though this cave was never completed.”

He explained that the cave’s design resembles the wooden huts that Buddhist monks lived in, which is why many believe it was occupied by Buddhists at some point. “Even though there are no Ashokan inscriptions here, its architectural style influenced later Buddhist caves like Ajanta and Karla,” he noted. “The arch is the key. This design spread far beyond this hill.”

The forgotten Ajivika Sect

“Ajivika,” he said, his voice growing softer as if sharing a secret. “They were a powerful sect back then. The founder, Makkhali Gosala, was once a companion of both Buddha and Mahavira, but you don’t hear much about them today. Under Ashoka and the Nandas, they thrived, but when the Mauryan Empire fell, so did their influence.”

He paused, looking around the silent caves. “Sadly, none of their texts survived. What we know about them comes from their rivals, the Buddhists and Jains, who didn’t have the kindest words for them. But these caves are their legacy.”

As we moved between the caves, the guide summed up the Ajivikas’ influence. “The Ajivikas may have disappeared, but their architectural legacy lives on. The caves here, especially the Sudama and Lomas Rishi, set the stage for rock-cut architecture in India. The chaitya arch from Lomas Rishi is the first of its kind, and from here, it spread to other parts of India.” These stones have seen empires rise and fall, and yet they stand, silent witnesses to a time long forgotten, just like the grand trunk road of India which passes through Bihar.

The caves and their nod to the past with inscriptions

Karan Chaupar cave

The first cave you encounter as you climb Barabar Hill is Karan Chaupar Cave. Its small rectangular doorway and stone-carved motifs immediately draw your attention. Near the entrance, an inscription in Brahmi script offers a glimpse into its history. There are two known translations of this inscription, both of which refer to Ashoka, also known as Priyadarsin. This confirms that the cave was built during his reign, specifically in the 19th year of his rule, around 250 BC.

Translation by E. Hultzsch (1925):

“In my 19th year of reign, I, King Priyadarsin, offered this cave of the very pleasant mountain of Khalatika, to serve as shelter during the rainy season.”

Translation by Harry Falk (2007):

“When King Priyadarsin had been anointed 19 years, he went to Jaluṭha and then this cave (called) Supriyekṣa, was given to the Ajivikas.”

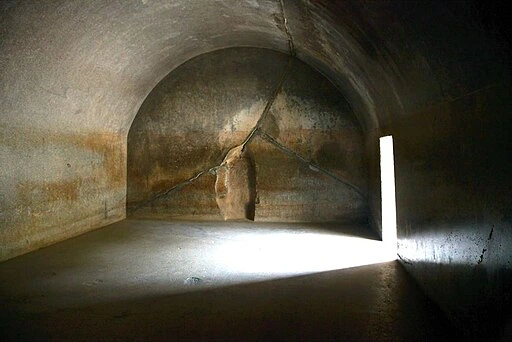

Inside the cave, there is a stone bench that historians believe was used for sleeping. The cave, like many others in Barabar, was likely used by monks for meditation and rest. The walls have a distinctive mirror-like polish, making the space even more fascinating.

Sudama cave

Heading left past Karan Chaupar, you’ll find Sudama Cave. This cave consists of two sections: a long rectangular room and a smaller, semi-circular chamber towards the front. The mirror-polished finish on the walls of the main chamber is so smooth that sunlight reflects inside, creating a glowing effect that feels almost otherworldly.

The echo inside the cave enhances the acoustics, adding a magical element to the experience. Speaking aloud within its walls, you can hear the sound circulate as if it has a life of its own.

Like Karan Chaupar, Sudama Cave also has an inscription in Brahmi script, which states:

“By King Priyadarsin, in the 12th year of his reign, this cave of Banyans was offered to the Ajivikas.”

This inscription further solidifies that Ashoka built these caves for the Ajivikas, a group of ascetics. The mention of the 12th year of Ashoka’s reign dates this cave to 257 BC.

Lomas Rishi cave

The most visually striking of the Barabar Caves, Lomas Rishi, features a beautifully carved stone arch at its entrance, known as a chaitya arch or Chandrashala. The intricate stonework on this arch is a masterpiece that commands admiration.

Above the arch, an inscription in Sanskrit reads:

“Om! He, Anantavarman who was the excellent son, captivating the hearts of mankind, of the illustrious Sardula, and who, possessed of very great virtues, adorned by his own (high) birth the family of the Maukhari kings,— he, of unsullied fame, with joy caused to be made, as if it were his own fame represented in bodily form in the world, this beautiful image, placed in (this) cave of the mountain Pravaragiri, of (the god) Krishna.”

This cave has two sections: a large rectangular room with the signature mirror-polished walls, and a smaller, oval-shaped room with a curved roof. While some historians argue that Lomas Rishi was built during the reign of the last Maurya emperor, Brihadratha, others believe it was constructed under Ashoka’s rule, with the ornate gateway added later.

Vishwakarma cave

Located about 150 meters away from the main set of caves, Vishwakarma Cave requires a bit more effort to reach. A small, unmarked road branches off from the right of Karan Chaupar, leading you through rocky terrain. After climbing the “Steps of Ashoka” carved into the rock, you arrive at the smallest of the four caves.

Instead of a traditional doorway, Vishwakarma Cave features a room-like section at the front with a narrow passage leading to a half-hemispherical chamber. The inscription at the entrance, written in Brahmi script, reads:

“By King Priyadarsin, in the 12th year (260 BC) of his reign, this cave of Khalatika Mountain was offered to the Ajivikas.”

Though it is the smallest, Vishwakarma Cave holds its own historical significance, with a distinctly unique layout compared to the other caves in Barabar.

Nagarjuni caves

About two kilometers from Barabar, Nagarjuni Hill hosts another set of caves—three in total. Unfortunately, due to time constraints, I only managed to visit Gopika Cave, which lies to the south. Vadathika and Vapiyaka Caves are situated towards the north, and I couldn’t explore them on this trip, but the promise to return lingers.

What makes the Barabar caves truly unique – Ancient innovation

Having explored many caves across India, I immediately see something unique about the Barabar Caves. While most ancient caves have the typical rough, rock-cut surfaces, the Barabar Caves boast walls with an almost mirror-like finish—something that’s incredibly rare, especially in ancient structures. It’s a feature we typically associate with modern architecture. So, it raises an intriguing question: how did the Barabar Caves, built over 2,000 years ago, achieve this flawless, polished finish?

Mirror finish – A marvel of ancient craftsmanship

The Barabar Caves are famous for their “mirror finish”—a technique so advanced that it seems almost unbelievable for its era. This finish was achieved by hand-polishing the granite to an extraordinary level of smoothness and reflectiveness. A mirror finish on granite creates a highly reflective, scratch-free surface, typically achieved today through mechanical polishing with abrasives and compounds. Yet, over 2,300 years ago, during the Mauryan Empire, this effect was accomplished by hand, demonstrating an incredible mastery of stone-working.

No one knows for certain how the Mauryans managed to achieve such a perfect finish. Some speculate that the imperial government’s sponsorship of the caves allowed for vast resources, manpower, and effort to create such a spectacular effect. The walls of the caves, particularly in the Sudama and Lomas Rishi caves, appear almost impossibly smooth, reflecting light in a way that gives the entire structure a surreal, polished appearance.

Persian influence and techniques

Interestingly, it’s believed that the know-how to create this mirror-like polish may have come from the Near East. Some archaeologists suggest that the polishing techniques used on the Barabar Caves resemble those found in Persian and Greek ruins. For example, the use of emery grains—extremely hard materials used for polishing stone—was common in regions like Naxos and Armenia. These regions, under the Persian Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC), were known for their stoneworking expertise.

In fact, several highly polished statues and artifacts from the Mauryan period, such as the famous Lion Capital of Ashoka, bear a striking resemblance to Persian Achaemenid craftsmanship. Archaeologists believe that after the Persian Empire fell to Alexander the Great in 330 BC, many displaced Persian and Greek artisans migrated to India, bringing with them their advanced stoneworking techniques, which were then sponsored by the Mauryan rulers.

Local innovations or imported expertise?

While there’s a strong argument for Persian and Greek influence in Mauryan stonework, it’s also possible that these techniques developed locally. Evidence of stone polishing exists in the pre-Mauryan Nanda period and the Indus Valley Civilization, where artifacts show a high level of polish. Neolithic tools such as polished stone axes further suggest that Indians were already experimenting with these techniques before the Mauryan period.

However, the distinctly Persian style of Mauryan artifacts and structures points to cultural exchange. The Barabar Caves likely reflect a blend of local innovation and foreign influence, making them not only a marvel of Indian architecture but also a symbol of ancient global collaboration in art and craftsmanship.

On the path to UNESCO World Heritage Recognition

If you’re curious whether a site as remarkable as this is recognized by UNESCO, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has taken steps to propose the Barabar and Nagarjuni caves in Bihar’s Jehanabad district for inclusion in UNESCO World Heritage sites in india tentative list of World Heritage Sites. These caves are regarded as the “oldest surviving rock-cut caves in India,” dating back to the Maurya period. The ASI’s Patna zone is currently preparing a detailed proposal, which will soon be submitted to UNESCO for consideration.

Beyond Barabar – Exploring hidden gems around the ancient caves

While exploring the Barabar Caves felt like stepping back in time into the world of E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, I knew my journey wasn’t over just yet. After immersing myself in the history of these ancient Indian caves, I wanted to discover more about the surrounding area. That’s when booking a Savaari came in handy—it made exploring nearby places so much easier. I arranged for a local car rental in Sultanpur and set off to visit some other incredible destinations around Barabar Hills. Here are a few spots you absolutely shouldn’t miss.

Vishnupad Temple – 34.2 km from Barabar Caves

The Vishnupad Temple is a sacred Hindu pilgrimage site, famed for the large footprint of Lord Vishnu housed within the temple. This ancient temple attracts pilgrims from across the country, particularly to Gaya. The surrounding areas like Suraj Kund, Akshaya Vat, Mangala Gauri, and Sita Kund are also popular religious spots, making Vishnupad a key destination for both Hindus and Buddhists. It is said that Lord Buddha meditated in this very location for many years, adding to its spiritual significance.

Dungeshwari Cave Temple – 39.4 km from Barabar Caves

Dungeshwari Cave Temple, also known as Mahakala Caves, holds a lesser-known but significant place in Buddhist history. Before attaining enlightenment, Lord Buddha is believed to have spent several years in these Indian caves during his exile. Today, these caves house temples and shrines that attract pilgrims and spiritual seekers who follow Lord Buddha’s journey. The mystical aura and peaceful atmosphere make it a unique stop for those seeking solitude and reflection. The caves feature both Hindu and Buddhist shrines, adding to their cultural importance.

Ratnaghara – 41.9 km from Barabar Caves

As part of the Buddhist pilgrimage circuit in Gaya, Ratnaghara holds deep significance for followers of Buddhism. It is believed to be the location where Lord Buddha emitted an aura of five colors after deep meditation, a story that attracts pilgrims from around the world. Located near the famous Mahabodhi Temple, this site offers a serene, spiritual experience for visitors exploring the roots of Buddhism.

Tibetan Monastery – 42 km from Barabar Caves

Located in Bodh gaya, the Tibetan Monastery is a peaceful retreat for those seeking tranquility. Established in 1938, it lies just across from the Mahabodhi Temple. The monastery features a massive dharmachakra (prayer wheel), which is believed to cleanse one of all sins when spun. Inside, you’ll also find images of Maitreya Buddha, the future incarnation of Lord Buddha, along with murals and artifacts of Tibetan Buddhism. It’s a serene and calming space, offering a perfect respite for travelers.

Barabar Caves – Where history and architecture unite

Bihar is home to some of the most stunning and historically rich sites, and the Barabar Caves are certainly among them. The breathtaking architecture and ancient craftsmanship offer a glimpse into India’s glorious past. To truly immerse yourself in the beauty of these caves and explore the surrounding gems, I highly recommend downloading the Savaari app.

With Savaari, you not only get to witness the ancient beauty of the Barabar Caves, but you also enjoy the flexibility to explore at your own pace, creating memories that will last long after the trip is over. Whether it’s tracing the footsteps of Lord Buddha or marvelling at the artistic legacy of Emperor Ashoka, this trip will be a profound connection to the past, brought to life with every stop.

Last Updated on October 26, 2024 by V Subhadra